With another flurry of deadline deals having come and gone, I got to thinking – no, not about whether Jazz Chisholm would kick-start the sluggish Yankees offense, or which team “won” the deadline – but about how this particular junction of the baseball calendar came to be.

After all, it’s not like Alexander Cartwright included a provision on trade deadlines when he (allegedly) codified the rules of baseball in 1845. On the other hand, for those among us who’ve been around long enough to remember the analog days of the 20th century, there was always a deadline in place. Did it just drop out of the sky like a big Bert Blyleven curveball?

It turns out that the deadline as we recognize it is the result of some factors that we also recognize – namely, the virtually open checkbook policies of a couple of rich New York ballclubs, although the primary culprit isn’t the one you’re imagining.

In 1917, the National League introduced the first trade deadline rule by mandating that players would have to clear waivers if they were sold or traded after August 20. This applied solely to the Senior Circuit, as the two leagues still often acted independently of one another at the time.

In the years that followed, Red Sox owner Harry Frazee and Yankees boss Colonel Ruppert engaged in a string of transactions that typically sent top-tier talent to New York and players plus cash to Beantown. After what turned out to be the most notorious of these deals – the sale of one George Herman Ruth to the Yanks completed in January, 1920 – American League owners came up with their own trade deadline of July 1 for the 1920 season. The following year, both leagues agreed to an August 1 deadline.

What happened next was predictable for anybody focused on baseball and not … I don’t know, speakeasies or flappers or whatever else people paid attention to in 1922. Following an early-year trade that brought 25-year-old infielder “Jumping” Joe Dugan to Boston, the Red Sox turned around and sent Dugan and outfielder Elmer Smith to the Yankees on July 23. At the time, the second-place Yanks were chasing the St. Louis Browns in the standings, and with Dugan apparently an upgrade over an aging Home Run Baker (although you couldn’t tell by looking at the stats), the Yanks went on to pass the Browns and win the pennant by one game, but eventually lose in the World Series to the Giants.

Ah yes, the Giants! The other New York club I alluded to earlier. Unlike the Yankees, who had acquired many of their impact players from the Sox in the offseason, the Giants had swung several midseason deals to boost their pennant hopes in recent years. Near the end of July in 1922, they sent three pitchers and the then-princely sum of $100,000 to the Boston Braves for right-hander “Handsome” Hugh McQuillan.

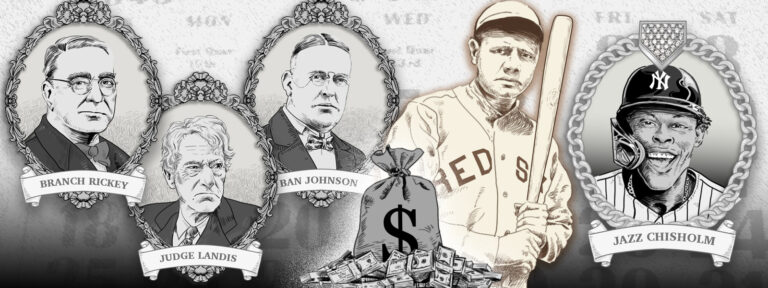

Again, with little but the numbers to go on, it’s hard to see how Handsome Hugh was such a difference-maker (or even how handsome he actually was) – he posted a 4.24 ERA before the trade, and 3.82 after. Still, this seemingly was the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back. It was easy for Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to ignore AL President Ban Johnson’s plea to abolish midseason trades altogether, since he hated Johnson. And then, respected Cardinals General Manager Branch Rickey was also complaining about the deals that seemingly gave deep-pocketed teams an advantage for the stretch run.

With other owners joining in the chorus, Commissioner Landis announced that June 15 would be the new, firm trade deadline for 1923. As with other mandates from baseball’s iron-fisted chief, this one held for decades, before being moved back to July 31 following the 1985 season.

And there it has largely held, save for a few tweaks to adjust for the deadline falling on a weekend or the occasional global pandemic, an arrangement that allows for moving today’s equivalents to Jumping Joe and Handsome Hugh and all the other players who partake in this annual midsummer game of musical chairs for both the deep-pocketed and the penny-pinching franchises.

Tim Ott

Tim's early yearnings for baseball immortality began on the dirt and grass of the P.S. 81 ballfield in the Bronx. Although a Hall of Fame career was not in the cards, his penchant for reading the MLB record book and volumes of history tomes led to an internship with MLB.com in 2002. Tim fulfilled an array of roles over the next nine years at the company, from editorial game producer to fantasy writer and editor and reporter for MLB-related promotions. While a busy freelance writing career has since taken him in other directions, Tim has always kept baseball in his heart, and is happy to be back to observing and reflecting on our great pastime.