The 2024 postseason has been a canvas calling to the artists who hold a bat in their hands, an invitation to paint thunderous and striking images of what can occur when a pitch nears the plate. The World Series alone will feature seven hitters coming off a 1.000-OPS line drawn from the League Championship Series: Dodgers Shohei Ohtani, Mookie Betts, Max Muncy and Tommy Edman; Yankees Juan Soto, Giancarlo Stanton and Anthony Rizzo. But even with all of the thunder and lightning effects soundtracking October baseball in 2024, odds are that when the final pitch is thrown and the trophy handed to the victors, the password for entrance into one of postseason baseball’s most exclusive and fun clubs will still be populated by the same tiny percentage of ballplayers that it had when the calendar read October 1, 2024.

This highly privileged phrase? “I hit .300/.400/.500 in my postseason career.”

The history of the AL-NL postseason has seen 388 players amass at least 100 plate appearances in the playoffs: by name, they stretch from Ronald Acuña Jr. to Ben Zobrist. Organized by way of good old fashioned batting average – lowest to highest – one starts and grimaces at Brandon Lowe’s .115 and then ends and exults in Paul Molitor’s .368.

And Molitor, as it happens, is one of just 10 – within that collection of 388 – to have the VIP password at his disposal.

Molitor didn’t exactly trample the competition in his first taste of postseason ball, batting .250/.318/.400 across five games in the 1981 ALDS. Across his next 24 contests, though, he resembled Rogers Hornsby in the 1920s, hitting .392/.459/.660 with that eye-blink slash of a swing, socking and spraying baseballs every which way. When all was said and done for the 1993 World Series MVP, he owned a .435 on-base mark and a .615 slugging stamp to accompany his .368 average.

Coincidentally, Molitor’s final entry to his postseason log came on the same night as another VIP member – Lenny Dykstra – struck his. In Game 6 of the 1993 World Series, as Molitor came within a double of hitting for the cycle, the Phillies’ center fielder was busy homering and walking twice to sign off on a slash line that featured a .321 average, a .433 on-base percentage and a .661 slugging percentage. “Ahh, sir, may I see your credentials? Ah, yes, very good, you may enter through the VIP entrance.”

Dykstra – as mostly a leadoff hitter in his 32-game postseason career – might be a surprise member of the 10. But to anyone who watched him in 1986, 1988 or 1993, big swings and big blasts with big results were a common occurrence. To quote myself, Dysktra – in October – was a slugger whose numerical signage looked comfortable sharing a room with the regular season career rates produced by Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg or Lou Gehrig.

I think of Greenberg and Gehrig – and Gehrig’s dynamic duet partner, Babe Ruth – along the refrain of the United States Postal Service’s unofficial motto, “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night …” you know how it goes. In any circumstance, within any kind of environment, when .300/.400/.500 is the spur of a conversation, these three are going to make their appointed rounds and then appear. As they do here.

The trio – doing all of their work in the World Series – challenged National League pitchers in a combined 418 plate appearances, with at least one of these three standing in the batter’s box in 17 of the 31 Fall Classics from 1915-1945. There was rarely a break for NL pennant winners over this stretch, and Ruth, Gehrig and Greenberg rarely went quiet into the dusk.

Ruth opened this destruction on his own, as the greatest solo act the game has seen, challenging conceptions, barraging through walls, brashly swatting away baseballs and all pre-existing notions of how exactly a batter’s box could be the starting point for generating offense. Once established in this mode, Ruth then shook hands with Gehrig and the two composed an unprecedented – and to this day, unsurpassed – benchmark for a 1-2 (or, if you’d prefer to nod to batting orders, 3-4) punch that set the numerical standard for the coterie being explored in this piece.

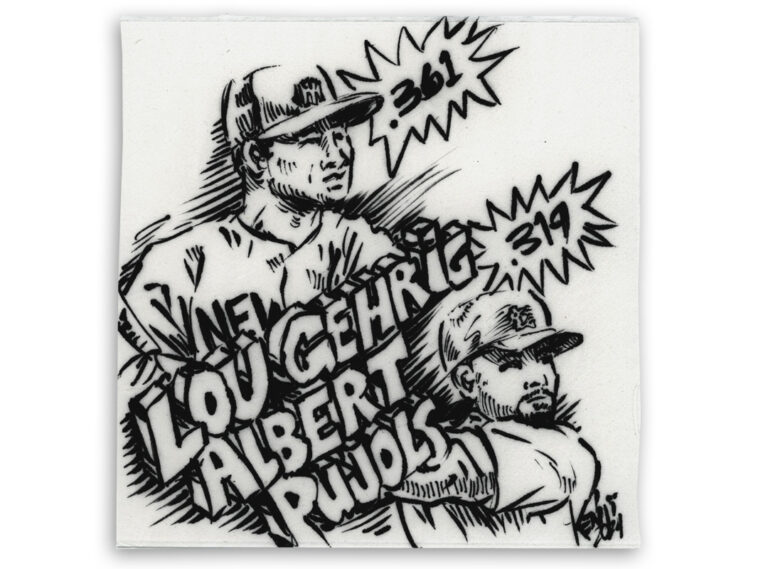

Ruth and Gehrig share – out to three decimal points – the highest OPS ever for any player in the postseason (min. 100 PA), at 1.214, and while together, won four pennants and a trio of titles. Those coronations often came with extra special demonstrations of their prowess.

In 1928, Gehrig compiled the highest OPS ever for a World Series (min. 12 PA) with a 2.433, topping Ruth’s 2.022 (which happens to be the fourth highest mark ever – oh poor, poor Cardinals hurlers). The Iron Horse wasn’t much of a slouch in 1932, either, when he posted a 1.718 but was overshadowed by Ruth deciding to – depending on who you ask and what you choose to see – call a shot or simply wave off the vitriol spewing from Chicago’s dugout. With a four-game sweep of the Cubs, the duet was concluded, as was Ruth’s postseason blockbuster: a franchise with 10 World Series appearances and a cumulative batting line of .326/.470/.744.

Now it was time for Gehrig to headline his own show in the Fall Classic theater. The man who could resemble a locomotive when hitting the basepaths after a ferocious swing claimed and contributed to three more titles from 1936-1938. His final stat line seems almost mythic: .361/483/.731.

Before Gehrig won those three final championships, though, Greenberg entered stage right and stepped into the role of leading man. For his intro, he met the Dean brothers – Paul and Dizzy – in 1934 and went .321/.406/.571 in a seven-game loss to the Gashouse Gang. Back in October the following year, he hardly had a chance to improve on his career line, dropping from the series in Game 2 after a slide at the plate resulted in an injured wrist. The Tigers’ icon would have to wait a few years to attempt his encore.

The 1940s brought two more spotlit chances, in 1940 and 1945, and although the decade was different, Greenberg’s influence from the batter’s box remained intact: imposing, daunting, potential energy converting to kinetic in a flash that could pulverize the ball. After he and Detroit claimed the 1945 World Series, Greenberg was forever the third member of the .300-.400-.500 club (no more World Series games for him), brandishing a career mark of a .318 average and percentages of .420/.624 in on-base and slugging. It would be a while before the VIP club had to open again.

When those doors were unlocked, another Yankee came calling. It wasn’t DiMaggio or Mantle who sauntered in, though, but Gene Woodling, who shared an outfield with both in the early stages of the 1951 Fall Classic. That ’51 World Series was smack in the middle of a five-year run for New York, when the Pinstripers won the title each and every year and Woodling had five chances to make his mark. By the time the Yankees defeated the Dodgers in 1953, Woodling had five rings, a .318/.442/.529 slash line to accentuate the jewelry, and the claim as leading New York in runs, hits, doubles, total bases, times on base and extra-base hits across the five-year span. As Woodling showed, postseason VIP status was available to more than just the baseball gods.

Gehrig and Ruth, Greenberg and Woodling … the four had the club’s quarters all to themselves for 40 years until Molitor and Dykstra put their finishing touches on their finishing lines and waltzed down the carpet. It was time for a new millennium to usher in a new collection of Fall Classic greats.

Thanks to Baseball Reference and its extraordinary research database, Stathead, for help in assembling this piece.

Roger Schlueter

As Sr. Editorial Director for Major League Baseball Productions from 2004-2015, Roger served as a hub for hundreds of hours of films, series, documentaries and features: as researcher, fact-checker, script doctor, and developer of ideas. The years at MLB Production gave him the ideal platform to pursue what galvanized him the most – the idea that so much of what takes place on the field during the MLB regular and postseason (and is forever beautifully condensed into a box score) has connections to what has come before. Unearthing and celebrating these webs allows baseball to thrive, for the present can come alive and also reignite the past.