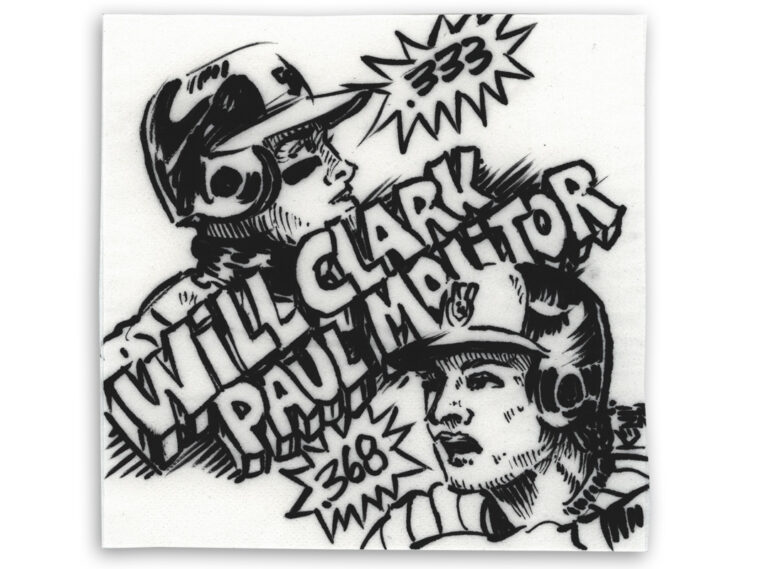

On the morning of October 3, 2000, the set of batters who could proclaim they ended their postseason careers with a .300/.400/.500 line (“ahem,” they might cough, “with at least 100 plate appearances”) numbered six: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Hank Greenberg, Gene Woodling, Paul Molitor and Lenny Dykstra. Later that same day, Cardinals first baseman Will Clark opened an eight-game fusillade that would vault him into a shared space with Ruth and the others and cap an astonishing postseason career. It was a fitting end for a thrilling experience that ignited its first charge during the 1987 NLCS and then escalated two years later.

Prior to the beginning of the ‘89 NLCS, Clark already owned a .360/.429/.560 line for his playoff résumé – a smoking start that was about to transform into the explosive. As he dueled swing for swing, wham for wham, swat for swat with Chicago first baseman Mark Grace, Clark pummeled Cubs pitching to the tune of .650/.682/1.200 with six extra-base hits in five games. There was a grand slam off Greg Maddux in Game 1 and in the clincher, a two-run single in the eighth to break a 1-1 tie and propel San Francisco to the edge of the pennant. That five-game display still resonates as one of the most comprehensive thwackings a postseason batter has ever inflicted upon the enemy.

Clark’s last ride – during the 2000 playoffs – was almost as astonishing, for it followed his Roy Hobbs-like tear after being traded to St. Louis in late July and gave us one last glimpse of the giant (and Giant) he used to be. The 36-year-old, with that gorgeous, worth the price of admission swing, sent baseballs tearing through the October air for a .345/.441/.621 line that pushed his final postseason numbers to .333/.409/.547. “The Thrill” was in the club.

The next year, another Cardinal began his own postseason novel – a tome that would ultimately cover 88 games across the span of 22 seasons and feature 10 different series with an OPS of at least .900. The apex – in terms of the OPS numbers – came in the 2004 NLCS, when Albert Pujols posted a 1.563. The apex – when it came to the curious ability to silence an entire ballpark with a swing – arrived in the 2005 NLCS, when the righty launched (or whatever a more powerful word for “launched” is) a Brad Lidge offering into what felt like a different realm. Pujols would claim an MVP award for his effort in 2004. He’d have immortality for that swing one year later.

The home runs and doubles and laser beams across the diamond would continue, having a final taste of sustained excellence in 2011: an 18-game, prize-winning effort in which he nabbed his second ring and slashed .353/.463/.691. The rest of the oeuvre wouldn’t be nearly as dashing or game-changing, but not everyone has a storybook ending to relate. Even with Albert’s quieter conclusion, the all-time great ended his postseason career with a .319/.422/.572 line in more than half a season’s worth of games. It was an epic story, full of extraordinary moments and tales of duels, like the one Albert once fought with the batsman from Houston, Carlos Beltrán.

Including his seven-game confrontation with Pujols in the 2004 NLCS, here’s what Beltrán did through his early exposures to the postseason crucible: 22 games featuring 11 home runs and four doubles among his 30 hits, 18 walks and 19 RBI, a rate stat joyride of .366/.485/.817. In that 20024 NLCS, while Pujols was posting his 1.563 OPS, Houston’s center fielder was right there with him, skipping along with a 1.521.

The switch-hitter made the playoffs his own playground, a wide expanse in which he could show off the batting equivalents of somersaults and flips, leaps and twirls. By the time he had more than doubled the 100-plate appearance threshold, Beltrán was still far in the clear of .300/.400/.500; the VIP carpet had all but been smoothed out and readied for his eventual stride toward the doors and a meet-and-greet with the other fellows. When he was finally able to say hello, he owned a .307/.412/.609 line and a side bet with The Babe as to who experienced the more deflating end to a playoff series: his backward K to finish the 2006 NLCS or Ruth’s caught-stealing to conclude the 1926 Fall Classic.

Beltrán is one of two switch-hitters keeping company in this VIP club, along with his (and Pujols’) one-time teammate, Lance Berkman.

“Ho-hum,” it began for the Astro in 2001, with a 2-for-12 effort in the 2001 NLDS that put a .167 in each of the three rate categories. After that, Berkman worked a different mode of consistency – one more meaningfully disruptive and eye-catching. Starting in 2004, Berkman scripted six straight playoff rounds with an OPS of no lower than .924 – five of the six produced a series-OPS above 1.000. This was Berkman, changing sides of the plate as fit the matchup but rarely wavering in how he produced in the box. The only noticeable alteration came in the difference between his regular season and postseason numbers, where his April- through- September rates all were slightly inferior to the ones he produced in October. If you’re going to change, this is a nice way to morph.

Through 2010, as the owner of a career .320/.419/.582 line in the postseason, Berkman was in position to ultimately be handed the VIP card for club membership. What he didn’t have in (or on) hand was a World Series ring to sparkle as he passed over the entrance ticket. The 2011 postseason changed that, with Berkman starring in event after event during one of the great contests in World Series history: Game 6, with St. Louis and Berkman facing elimination.

He homered in the first to turn a 1-0 deficit into a 2-1 lead. He scored the game-tying run in the fourth. He scored another game-tying run in the sixth. He did it yet again when he crossed the plate in the ninth to make it a 7-7 game (ahh, the consistency was back in action). Finally, in the bottom of the 10th with St. Louis down by one and down to their final out, Berkman decided to change the score by swinging rather than running. RBI single to center, game tied. A David Freese homer in the following frame moved Berkman one win away from the title. The next night, he had his championship affirmation and a completed postseason line: .317/.417/.532. Come on in!

That’s the 10 – Ruth, Gehrig, Greenberg, Woodling, Molitor, Dysktra, Clark, Berkman, Beltrán and Pujols – the only batters in AL-NL postseason history who called it quits and could look back at 100+ plate appearances and a .300/.400/.500 line – those lines granting access to the VIP club where shining numbers meet unforgettable moments and swings to animate and populate and invigorate the magic of baseball in October.

Note: Randy Arozarena – last seen patrolling left field for the 2024 Mariners – owns a .336/.414/.690 line in 128 postseason plate appearances. But until we know there’s no more to come, the VIP doors remain closed to him.

Thanks to Baseball Reference and its extraordinary research database, Stathead, for help in assembling this piece.

Roger Schlueter

As Sr. Editorial Director for Major League Baseball Productions from 2004-2015, Roger served as a hub for hundreds of hours of films, series, documentaries and features: as researcher, fact-checker, script doctor, and developer of ideas. The years at MLB Production gave him the ideal platform to pursue what galvanized him the most – the idea that so much of what takes place on the field during the MLB regular and postseason (and is forever beautifully condensed into a box score) has connections to what has come before. Unearthing and celebrating these webs allows baseball to thrive, for the present can come alive and also reignite the past.