Sometimes, when thinking back to my childhood in the early 1980s, I try to remember how a young baseball fan followed the sport’s top athletes in those pre-cable, pre-internet days.

Magazines like Sports Illustrated kept us in the loop, along with NBC’s nationally televised Game of the Week and other kid-friendly programs like This Week in Baseball and The Baseball Bunch. Baseball cards did the trick, too, as they provided an array of statistics and trivia, although I was more into the short-lived sticker albums.

However we did it back then, I remember being transfixed by a few players who didn’t suit up in the pinstripes of my favorite team. Dale Murphy was clearly a stud down in Atlanta. Steve Carlton was the epitome of a dominant pitcher in Philadelphia. And way out west in Oakland, there was a player resplendent in white and green who always seemed to be diving head-first into a base.

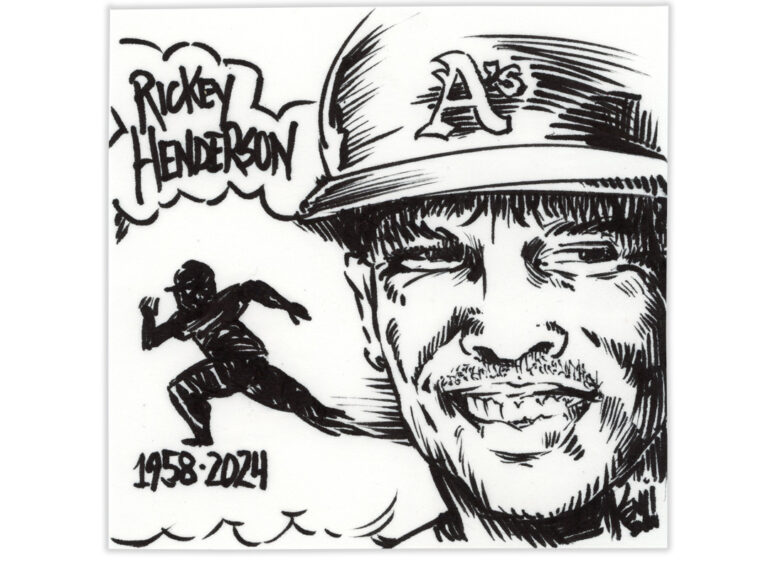

Actually, it’s difficult to imagine any baseball fan being unaware of Rickey Henderson’s brilliance at that point in time. In 1982, he set a Major League record with 130 stolen bases. The home run has long been the signature individual triumph for a player, from little league to the highest professional rung, but the stolen base has its own special place in the hierarchy of successes with its dependence on speed and daring. And even a six-year-old understands the significance of a number being a Major League record.

A little more than two years later, the West Coast speedster was traded to the Yankees, and with the move, the man who had formerly been a conglomeration of stolen base numbers and photos became a flesh-and-blood ballplayer to watch on a regular basis.

What I remember about Rickey from those years was a man who was seemingly in a perpetual crouch. He famously hunched over at the plate, shrinking his strike zone to about 10 inches in height – a clear lesson for a little leaguer to emulate, even if the men in blue calling balls and strikes behind me weren’t buying it.

Rickey was also always crouching in one of his countless leads off the bases, but even in times when the situation didn’t call for it – while gliding around the bases after a home run or whipping off a patented “snatch catch” – he often seemed to be half-hunched over, as if cruising on a lower gear and coiled to spring to action, if necessary.

I was disappointed that Henderson stole “only” 80 bases in that first season with the Yanks – Vince Coleman would emerge as the reigning burner that year with 110 swipes – but overall the numbers were stunning: a .314 average, 99 walks, a career-high 24 homers, an incredible 146 runs scored. I wasn’t going to argue with Donnie Baseball claiming the MVP on the strength of 145 RBI, but now that we can see that Henderson led the AL with 9.9 bWAR, I think it’s safe to say that most of us underestimated his impact that year.

Henderson was better in some superficial ways in 1986, bumping his steals up to 87 and his homers up to 28, but he was hampered by hamstring injuries in 1987 and his power vanished in ’88, even as he nearly reached 100 steals one more time. This was a frustrating time to be a Yankees fan, as they went from being just out of the playoffs in ’85 to good but clearly not good enough within a couple of years, and the decline seemed to wear on its one-of-a-kind leadoff man.

The scuffling Yanks sent Henderson back to the A’s before the halfway point of the 1989 season, and the dynamo was suddenly reignited: He slashed .247/.392/.349 with 25 steals in 65 games before the trade, and .294/.425/.438 with 52 swipes in 85 games for the eventual World Series champs after. This presented another lesson for an impressionable big league hopeful: sometimes, a player’s performance rises and falls depending on the environment he inhabits.

But there were no lingering hard feelings about Rickey’s inability to rediscover the golden touch until returning to Oakland; sometimes you just want to see the great ones continue doing what makes them so special. Fans were certainly treated to Rickey in peak form in 1990, when he notched personal bests in average, OBP and slugging to lead Oakland back to the World Series and earn a well-deserved MVP Award. The following year brought the inevitable when he swiped third against the Yankees in early May to surpass Lou Brock’s record for 938 steals and infamously declare himself as the “greatest of all time.”

It’s fitting that Henderson set the record when he did because baseball was on the cusp of a new era. Two new expansion teams appeared in 1993, prompting divisional realignments the following year, before two more teams arrived in 1998. The playoffs also underwent an overhaul with the introduction of the non-division wild card winner in 1995, one year after the World Series was canceled for the first time in 90 years. Between the lines, stolen bases were trending downward, while power numbers would reach unseen levels in the game’s history.

Amid all the changes, Rickey kept doing what he always did, even as age began to ever so slightly slow his legs and the carousel of trades and free agency seemingly never kept him in one city beyond a season or two. Every once in a while I would turn on a now easily accessible cable TV channel and see him in a strange uniform – whether for the Padres, Angels, Mets or Mariners – but otherwise looking mostly the same, his face a little more lined but biceps as buff as ever, as he settled into that crouch in the box.

Back then, before my own face was showing too many lines, the concept of an aging star recapturing his past glory for a year didn’t seem particularly far-fetched. Now that I know better, it’s mind-boggling to consider that in 1998, when he was 39 years old, Henderson led the AL one final time with 66 stolen bases (as well as 118 walks). The following year – at 40, to hammer home the point – he slashed .315/.423/.466 with 37 steals in 121 games.

Rickey couldn’t play forever, but he sure as hell tried. Unable to find a big league taker by the start of the 2003 season, the 44-year-old signed on with the Newark Bears of the independent Atlantic League; a .339/.493/.591 slash line over 56 games with that club earned him a late-season stint with the Dodgers. He then spent all of 2004 with the Bears and the 2005 season with the San Diego Surf Dawgs of the Golden League, but there would be no return to the Show; after 25 seasons, his big league career was finished.

The lifetime numbers, of course, are staggering: his 2,295 runs scored and 81 leadoff home runs are MLB records, while his 2,190 walks have since been surpassed by Barry Bonds. He’s fourth all time in games played and total times on base, reached 3,000 hits and accumulated 111.1 bWAR, good for 19th on the all-time list between Lou Gehrig and Mel Ott.

But with Rickey, it always comes back to the stolen bases. A 12-time league leader in that category, his career total of 1,406 is so far ahead of the rest of the pack, it stands out from the record book in the same manner as Cy Young’s 511 wins; a curious, incomprehensible number from a bygone era.

Strangely, for a person known for his quirky personality and Rickey-isms, the baseball great was unusually quiet in the two decades after he hung up his cleats. He wasn’t active on social media, to my knowledge, and he didn’t surface as a talking head on TV. Following his return to the limelight with his induction into the Hall of Fame in 2009, he quickly retreated from view like a bench player after an 0-for-4 night.

And in the end, maybe it’s better that way. Some athletes stick their feet in their mouths with their tweets, unnecessarily riling up fans and diminishing their legacies. With Rickey, we can simply marvel at the numbers and recall the thrill of seeing him in action, when the impulse strikes us.

Rickey Henderson would have turned 66 on Christmas Day. Of course, age never quite applied to this man the way it did for so many athletes, and whether he was running wild for the A’s in his early 20s or leaning on his veteran know-how a quarter-century later, we can easily recall him in that all-too-familiar crouch, ready to unload on a pitch that squeezed into his bite-sized strike zone, or to take off for that base so tantalizingly close at less than 90 feet away.

Thanks to Baseball Reference and its extraordinary research database, Stathead, for help in assembling this piece.

Tim Ott

Tim's early yearnings for baseball immortality began on the dirt and grass of the P.S. 81 ballfield in the Bronx. Although a Hall of Fame career was not in the cards, his penchant for reading the MLB record book and volumes of history tomes led to an internship with MLB.com in 2002. Tim fulfilled an array of roles over the next nine years at the company, from editorial game producer to fantasy writer and editor and reporter for MLB-related promotions. While a busy freelance writing career has since taken him in other directions, Tim has always kept baseball in his heart, and is happy to be back to observing and reflecting on our great pastime.